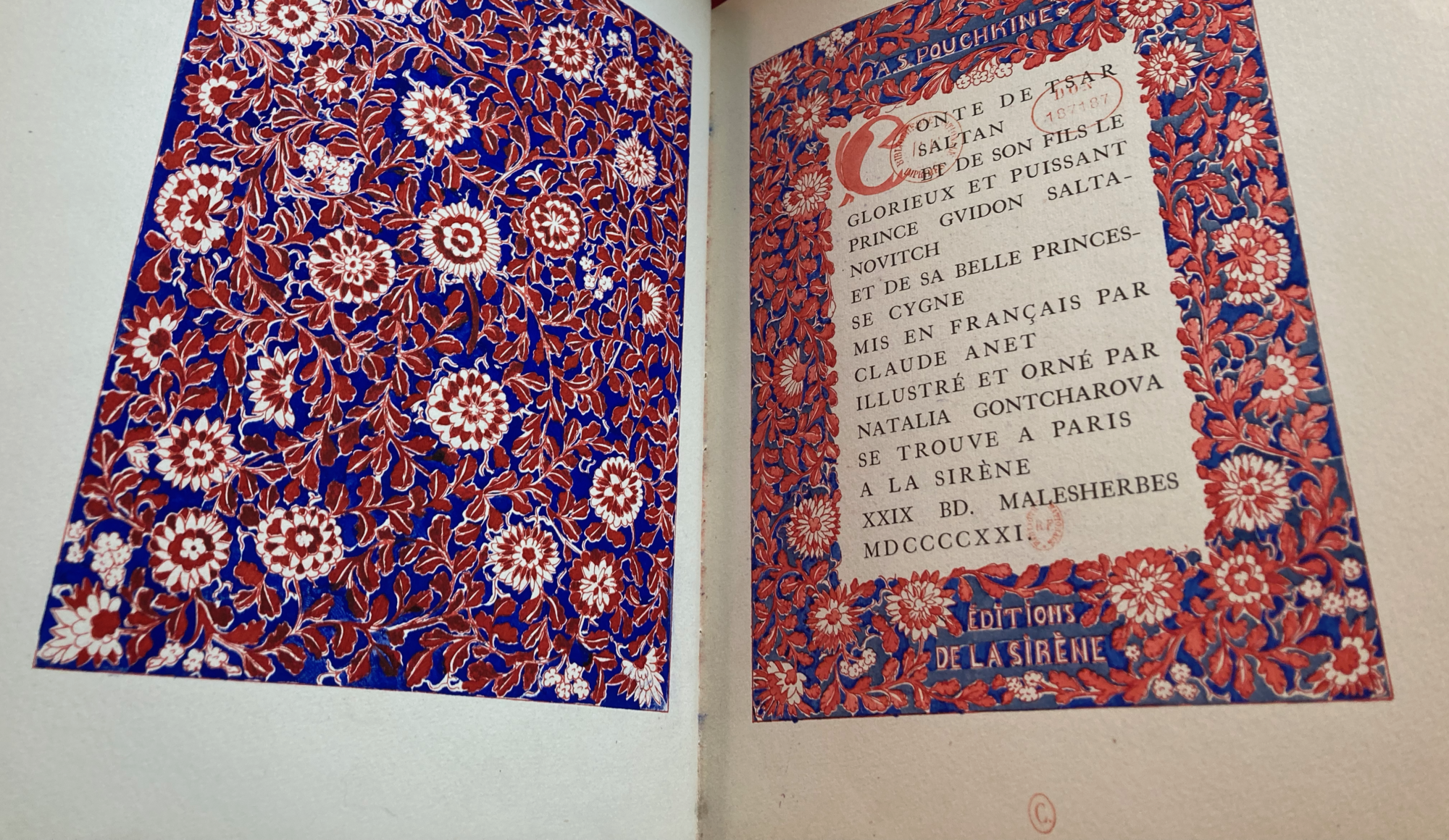

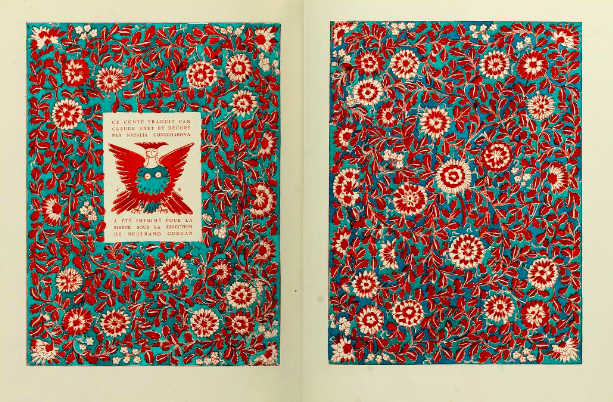

PUSHKIN, Alexander Sergeevich. Le Conte de Tsar Saltan. Translated from Russian by Claude Anet. — Paris, Editions de la Sirène, 29 Bd. Malesherbes, (25 May) 1921. Printed by Louis Kaldor; images colored by the ateliers Marty under the direction of Daniel Jacomet; the edition was printed under the direction of Bertrand Guéga.

Quarto (290 x 220 mm). 54 pp., 10 full-page pochoir plates, with Goncharova’s coloured initials, vignettes, frames, covers and endpapers. Limited to 599 copies.

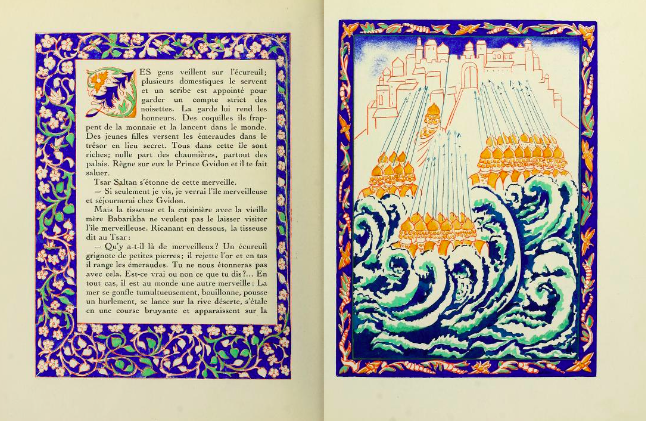

This tale in verse by Pushkin was written in 1831 and first published the following year in his collection of poems. It recounts the story of King Saltan’s marriage and the birth of his son, Prince Gvidon, who because of his aunts’ shenanigans ends up on a deserted island where he meets the enchanting Princess Swan, with her help becomes a powerful ruler and is reunited with his father.

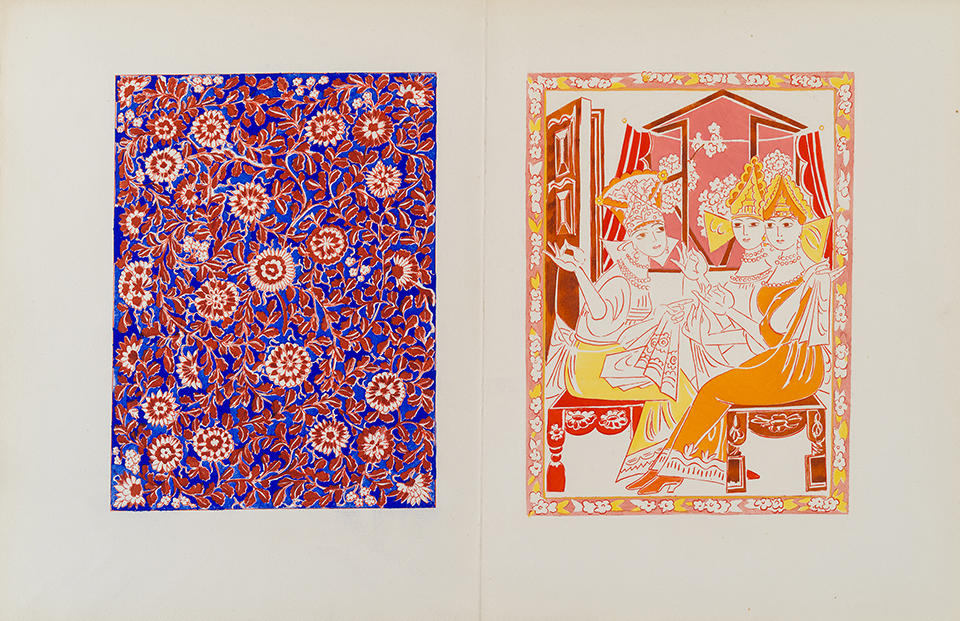

For the edition, Goncharova created twenty-nine original initials, ten full-page narrative illustrations, and six full-page color ornaments with images of flowers; the remaining pages of the tale text appear in floral multicolored frames. The images were coloured at the atelier of Daniel Jacomet, one of the leaders in pochoir, the hallmark of attractive coloring in the 1920s.

In her work, she depicts the fairytale characters and scenes by simplifying the graphic form, employing a flat background, and featuring a play of colors that all together resemble lubok, the folk print technique, popular in the Russian Empire. Such a decorative effect had been intrinsic to most of the paintings by Goncharova in Russia. In her essay about Goncharova, poet Marina Tsvetaeva quotes the artist: “Decorative painting? Poetic poetry. Nonsense. Every painting is decorative, since it decorates and paints”. The commission to create book illustrations –– the medium which initially gravitates towards a decorative form –– fulfilled Goncharova’s ideas about ‘decorativism’ and folk (lubok) art.

Interestingly, the original title of Pushkin’s tale Conte de tsar Saltan et de son fils le glorieux et puissant prince Gvidon Saltanovitch, et de sa belle princesse Cygne imitates the commonly long titles of fairy tales and bogatyr-knight stories in lubok popular books. In the country, according to Goncharova, an artist can find intrinsic national forms, dating back to prehistoric times and then evolving through the religious Middle Ages. Goncharova considered Russian icon painting the highest achievement of Old Russian aesthetics; she recognized the uniqueness and autonomy of medieval icons and she saw many paths for its continuation in modern times and particularly, in folk art. Her illustrations of Pushkin’s fairytale embody these principles she developed while still in Russia.

Goncharova’s illustrations for Le Conte de Tsar Saltan represent the combination of influences from the Russian, Eastern and Western cultures on the artist. Looking at her images for Pushkin’s tale, we can easily recognize some influences from her earlier works. In his book Russian Art at the Beginning of the 20th Century: Image of Russia, Gleb Pospelov, argues that Goncharova’s illustrations for Pushkin’s tale demonstrate the influence of European art and culture on the artist. He writes that the illustrations, in their abundant decorative elements and compositions, ressemble not the images from Russian folk art but the French tapestries from the Cluny Museum and particularly, The Lady and the Unicorn that Goncharova certainly saw while in France.

- L’art décoratif théâtral moderne

- Samum

- Motdinamo

- Transparent Shadows and Forms

- Twelve. Scythians.

- Gorod (City)

- Conte de Tsar Saltan

- The Russian Ballet in Western Europe 1909-1920

- Tale of Prince Igor

- L’Annonciation: Roman

- Le thé du capitaine Sogoub

- Les Montparnos

- Les Ballets Russes de Serge de Diaghilew

- Skazki (Fairytales)